Carolina Maria de Jesus pt 2: Poverty as Main Character

“Xmas Day. Joao came in saying he had a stomach ache.

I knew what it was for he had eaten a rotten melon.

Today they threw a truckload of melons near the river.

I don’t know why it is that these senseless business men come to throw their

rotted products here near the favela, for the children to see and eat.”

-Carolina's diary, December 25, 1958

In order for one to be present with the diaries of Carolina Maria de Jesus, it is imperative that the reader obtain an understanding of and empathy for the socioeconomic position from which she was documenting herself. Living in the slums of Sao Paolo, Dona (a Brazilian title similar to “Ms./Mrs.” or “ma’m”) Carolina wrote her diary as an aching voice decrying the injustice of disenfranchisement and the design of poverty as she bore witness in the favela of São Paolo Brazil. The favela: an outskirts, blighted wasteland of slums and shack domiciles essentially stacked atop of one another. The favela is most popular for its ultimately inhumane conditions incubated by the government’s malignant neglect— brawls, noise levels, lawlessness, restricted utilities, hunger, and close proximity that makes privacy nearly impossible. If that sounds like low income housing, then congratulations! you’re beginning to realize why Carolina’s journal is a testimony indicting the entire western system and not just a record of her life. Carolina’s entries didn’t mince words regarding the favela’s dehumanising environment: the name of her first published diary is “Quarto de Despejo”—the garbage room. Carolina’s semi-daily chronicles of her life’s severity and coarseness are shaped by her insights on the experience of living in poverty as a Black single mother. This understanding HAS TO frame how you handle her diary. You must understand the design and violence of poverty as endured by a Black single mother.

Like poverty, single motherhood in Blackness is a form of violence, though, to maintain the JimCrow propaganda of the animalistic mammy Black woman in the white psyche, Black single motherhood is never framed as deleterious, unnatural, or violent. This is why there is no consistent, systemic language framing it as a harmful dynamic, but plenty of media portraying Black women as “strong” single mothers. It behooves this society to have only ONE feminine being, and that can only be the ever-innocent, rescue-ready, straight white female. Society programs YOU to see she in her ghostly paleness as in need of saving and protection while diagnosing Black women as ONLY ever existing in consequences. In summation, Carolina Maria de Jesus’ diary was nearly buried in history because society worldwide finds Black single mothers as immaterial, nugatory beings living as thralls and producers of negative statistics. However, we must dismantle this construct and recognise that the societal violence endured by Black single mothers is a precursor to the violence coming for us ALL. Whether she is of means or not (usually not), there is something sinister about society being willing to observe a Black woman raise children alone to stigma, isolation, single income and the conspiracy of unquestioned pariah status that calls us all to examine ourselves. We have been brainwashed to appreciate her lone, polymelian experience without creating resources to ameliorate the state of raising children alone while being Black and woman.

If you’d like to read more about the connections between violence, poverty and Black single motherhood, I wrote on this very subject as part of an essay series for Loving Black Single Mothers.

To repeat what you have been socialised to intentionally misunderstand and turn a deaf ear to: one cannot examine Carolina Maria de Jesus’ notebooks without holding at the forefront of the mind the evils of a judge-and-jury society weaponised against Black single mothers— especially those living in poverty. Black single mothers are the SOLE single-mother status whose socioeconomc barriers and obstacles are politically and media-sanctioned; whose stigmas and propaganda brainwash ALL people groups to observe their plight with indifference, blame, blind indictment, and paltry “compliments” that render the systemic violence she endures unseen and necessary. I believe this unchallenged mindset is what frames the headspace of most readers of Carolina’s notebooks: the judgement that her children being from multiple fathers implies that her impoverished status was warranted is the violent stigma ALL Black single mothers live through. Those who believe a slum is a just sentence for a woman raising three children from different fathers are more common than not. Furthermore, considering Brazil’s NOTORIOUS post-chattel slavery, racialized caste system, Carolina’s endurance through motherhood must be revered for its indefatigability. Dona Carolina deserves to be respected not only as a diarist/author but with the pathos of a woman who saw publishing her private thoughts as the most dignified avenue to providing a better life for her children. If she was a blonde haired, blue eyed, straight white male, her selling paper scraps and writing in discarded journals while cooking vegetables she found in the garbage would be heralded as the hero’s arc; a valorous journey, with countless movies and Netflix series created to trumpet the bravery and resiliency. That we all know this speaks to our awareness of the networks of systemic violence counteracting not only resources but also care of Black single mothers.

“I have lost eight kilos. I have no meat on my bones, and the little I did have has gone.

I picked up the papers and went out. When I went past a shop window I saw my reflection.

I looked the other way because I thought I was seeing a ghost.”

— diary entry, July 15, 1959

“when I got home, I was starving. My cat came around meowing.

I looked at him and thought: I never ate cat, but if he were in a pan,

covered with onions and tomatoes, I swear I’d eat him.

Hunger is the worst thing in the world.

I told the children that today we were not going to eat. They were unhappy.”

— diary entry, July 31, 1959

In all of the writings I’ve come across online about Carolina, not ONE has spoken to her AS a Black single mother. She’s a diarist who happens to have children, but the psychological determination and fortification of herself as a Black mother raising children alone is never explored. I want to give Dona Carolina this honour today. It is no minute thing to endure the emotional and psychological battery of raising children in a slum, the mind daily racing to ideate means of feeding them (TWO BOYS at that— you know about boys’ appetites, yes?) with no money on hand, then enduring the daily humiliation of being a favelado and lacking the essentials to provide a dignified home for yourself and your children. Carolina didn’t JUST write a diary. She wrote about deworming her children, about saving her daughter Vera from a child-molester who had been stalking the girl, about not being able to find her son for a couple of days, about being happy to have enough money to give them meat WITH their rice and beans and coffee— and about telling them that there would be no food that day, and perhaps the next. This is a mother enduring brutal anguish in the labyrinth of destitution and Black singlemotherhood. We see her write of suicidal thoughts, despising her children, and fearing for what they might become because of all they’d been exposed to in the raucousness of the favela. These are feelings we have to feel as well as we read her notebooks. This woman did all she was doing NOT for fame and fortune—but to keep her children alive while nurturing her Divinely-instilled gifts. Her notebooks have preserved her valiant buzz amongst motherhood, primitive cultural anthropoligical work, cultivation of self; and both witnessing against and navigating poverty’s violence.

“For supper I prepared beans, rice, and meat. Vera is so happy because we have meat!”

—Carolina’s diary, May 7, 1959

“When I got out of bed, Vera was already awake, and she asked:

‘Mama isn’t today, my birthday?’

‘ It is. my congratulations. I wish you happiness..’

‘Are you going to make a cake for me?’

‘I don’t know. If I can get some money…’

… I fried fish and made some corn mush for the children to eat with the fish. When Vera showed up and saw the mush inside the pot, she asked:

‘Is that a cake? Today is my birthday!’

‘No it isn’t a cake. It’s mush.’

I got some milk. I gave her milk and mush. She ate it, sobbing.

Who am I to make a cake?”

— Carolina’s diary, July 15, 1959

Framing the Notebooks

“Lentils are 100 cruzieros a kilo, the fact that pleases me immensely.

I danced, sang and jumped and thanked God, the judge of Kings!

Where am I to get 100 cruzieros? It was in January when the water’s flooded the warehouses

and ruined the food. Well done rather than sell the things cheaply,

they kept waiting for higher prices. I saw men throw sacks of rice into the river.

They threw dried codfish cheese and sweets. How I envied the fish who didn’t work but lived better than I.”

— diary entry, June 13, 1958

“It's raining. I am almost crazy with the dripping on the beds,

because the roof is covered with cardboard, and the cardboard is rotten.

The water is rising and invading the yards of the favelados.”

— diary entry, January 5, 1959

Carolina’s horror-strewn LIFE confirms that poverty is absolutely political, and absolutely by state-sanctioned design. The tediousness of her journey is repeatedly noted in her diary almost to the state of eroding the reader’s mind, and as the readers we must employ the honour of empathy to anatomise the “missing parts” of her sad testimonies adding the muscle, bone, blood and flesh of context to the situational dynamics to which she was testifying. Most of us already understand the implications to high cost of living, high grocery prices, the pay check to paycheck limbo, and the strain of being one inconvenience away from all financial stability being broken. Dona Carolina was living far past this point: she was living in slums, in destitution; her chidren begging or rummaging in the garbage for edible scraps of food. Understanding her as a nonfiction, dark-skinned (important; she could not pass for white or appease whiteness with hesitantly-melanated skin) Black woman, single mother, and a descendant of the Middle Passage (not an African immigrant to Brazil), means framing every element of her world so as to understand her motive, her pain and her lived, posthumous mandate. This is the humanity from which Black women are robbed in their lives: being understood IN context. We have Carolina’s diary not only to read but also to utilise as reference material; as plumbline,as a means of telling our own times, realizing the commonalities and overlaps between the dynamics, conspiracies and injustice she navigated and those that characterise our lives today as Black people. Poverty and systemic racism are the antagonists in her story, while her journal is the embalming agent, preserved her ideas through the generations so that we can approach and engage her words and be empowered to act as a continuance of liberation.

Dona de Jesus endured the anguish, dejection and violence of poverty in the unfortunately infamous favela of Sao Paolo, Brazil: a confined zone of mire and desuetude where the caste-aways of society find themselves discarded via racism, hyper-policing and kept in said place by systemic disenfranchisement— identical to what we’d call the ghetto or the projects today. Like any ghetto, the immoral, deleterious blueprint of the favela, is designed to suffocate upward mobility, maintain social stigma, and enforce racialised ideas of white supremacy to those living outside of it, who feel morally exceptional to those whose destinies they have intercepted through colonisation, gentrification. Ghettos are doctored evidence in western society; confined and derelict, they are what Kenneth B. Clark describes as having “invisible walls [that have] been erected by the white society, by those who have power, both to confine those who have no power and to perpetuate their powerlessness.” With scathing language, Clark continues in his sharp, sociological summation:

“The dark ghettos are local, political, educational, and—above all— economic colonies. Their inhabitants are subject peoples, victims of the greed, cruelty, insensitivity, guilt, and fear of their masters…

The Negro [is]…confronted by a harsh world of reality where the dreams do not come true or change into nightmares. The discrepancy between the reality and the dream burns into their consciousness. The oppressed can never be sure whether their failures reflect personal inferiority or the fact of color. This persistent agonising conflict dominates their lives.” (Clark, pp. 11-12)

In his book THE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH, (which he wrote in 1961, one of the years Carolina was recording in her diary!) Frantz Fanon explains the sinister, premeditated motive to the creation of such dehumanising areas:

“The town belonging to the colonised people…the Negro village, the medina, the reservation, is a place of ill fame, peopled by men of evil repute… It is a world without spaciousness; men live there on top of each other, and their huts are built one on top of the other. The native town is a hungry town, starved of bread, of meat, of shoes, of coal, of light… [it is] a crouching village, a town on its knees, a town wallowing in the mire.” (Fanon, p.39)

Corroborating Fanon later on, Kenneth B. Clark would provide the key elements of a ghetto, the traits and dynamics of which we repeatedly observe in Carolina’s diary. Clark offers:

“The symptoms of lower-class society afflict the dark ghettos of America— low aspiration, poor education, family instability, illegitimacy, unemployment, crime, drug addiction and alcoholism, frequent illness and early death.

…The most concrete fact of the ghetto is its physical ugliness—the dirt, the filth, the neglect. In many stores walls are unpainted, windows are unwashed, service is poor, supplies are meagre. The parks are seedy with lack of care. The streets are crowded with the people and refuse…. [In Harlem there are] hundreds of bars, hundreds of churches, and scores of fortune tellers. Everywhere there are signs of fantasy, decay, abandonment, and defeat. The only constant characteristic is a sense of inadequacy.

…The dark ghetto is not a viable community. It cannot support its people; most have to leave it for their daily jobs… The ghetto feeds upon itself; it does not produce goods or contribute to the prosperity of the city.” (Clark, p. 27)

“lately it has become very difficult to get water, because the amount

of people in the favela has doubled. And there is only one spigot.”

— Carolina’s diary, August 12, 1958

Furthermore, in his incendiary autobiography REVOLUTIONARY SUICIDE, Huey P. Newton echoes Fanon’s sentiments and with more explicit language, affirms that the situation of marginalised peoples in slums, favelas, ghettos, and other blighted areas is indicates the presence of an insidious, racialised, systemic design be it through starvation, lack of infrastructure, or unemployment. Regard Newton’s indicting description of where he was raised, “the other Oakland”:

“The other Oakland—the flatlands—consists of substandard-income families that make up about 50 percent of the population of nearly 450,000. They live in either rundown, crowded West Oakland or dilapidated East Oakland, hemmed in block after block, in ancient, decaying structures., now cut up into multiple dwelllings. Here the majority of Blacks, Chicanos, and Chinese people struggle to survive. The landscape of East and West Oalkand is depressing; it resembles a crumbling ghost town, but a ghost town with inhabitants, among them over 200,000 Blacks, nearly half the city’s population.” (Newton, p.13)

Clearly there is a pattern here. Funny enough, Fanon wrote WRETCHED in 1961 (it was published in 1968)—the last year dating Carolina’s handwritten notebooks. Notably, it’s no coincidence that she, Fanon, Clark and Newton have overlapping published indictments of the situation and tribulation poverty creates for those of the global majority. Every place that has been colonised is marked by racialized segregation of classes, where mainly Black peoples are marginalized to enunciatedly derelict areas of socioeconomic condemnation. Kenneth B. Clark defines the intentional parameters of the ghetto and the light of human resilience stirring within it:

“The objective dimensions of the American urban ghettos are overcrowded and deteriorated housing, high infant mortality, crime and disease. The subjective dimensions are resentment, hostility, despair, apathy, self-depreciation, and its ironic companion, compensatory grandiose behaviour…

The ghetto is hope, it is despair, it is churches and bars. It is aspiration for change, and it is apathy. It is vibrancy, it is stagnation. It is courage, and it is defeatism. It is cooperation and concern, and it is suspicion, competitiveness, and reaction…

The pathologies of the ghetto community perpetuate themselves through cumulative ugliness, deterioration, and isolation and strengthen the Negro’s sense of worthlessness, giving testimony to his impotence… Those who are required to live in congested and rat-infested homes are aware that others are not so dehumanized.” (Clark, pp. 11-12)

The circumstances are perfectly described in Newton’s explaining that “The Black communities of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Newark, Brownsville, Watts, Detroit and many others stand s testament that racism is aso oppressive in the North as in the South.” Carolina’s notebooks force us to expand this as Northern and Southern portions of the Western hemisphere: The racism is the same in USA as it is in Brazil. Newton continues, “The poor know better and they will tell you a different story.”(p.12) illustrating a setting similar to the world we enter when we commence Carolina’s journals:

“Oakland has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country, and for the Black population it is even higher… Because of the lack of employment opportunities in Oakland today, the number of families on welfare is the second highest in California… The police department has a long history of brutality and hatred of Blacks. Twenty-five years ago official crime became so bad that the California state legislature investigated the Oakland force and found corruption so pervasive that the police chief was forced to resign.” (Newton, p.13)

Such world flanked and flogged Carolina Maria de Jesus. Fully aware of the long-standing impact on she and her children’s lives, Dona de Jesus wrote both THROUGH and AGAINST the favela’s treacherous geography and cocktail of violence with miraculous literacy and arresting language. Her journal entries captured the elements of her environment through daily observations, political opinions, memoire notes, historical notations, social commentary and poetry. Now, there were also days where she couldn’t write; she wasn’t always strong enough to blaze onward as erudite witness due to either or a combination of starvation, anxiety, and/or sadness. Generally speaking she understood the power of her presence with her notebook and the importance of her written testimony against poverty, agents of systemic violence, and the favela itself. Understanding the magnitude of the opportunity presented to her to not just document her life but to decry the design of violent systems that kept favelados imprisoned and the poor, poor, she wrote as herself with generation-spanning precision.

“[Senhor Dorio] must learn that Arvella [favela] is the garbage dump of São Paulo, and I am just a piece of garbage.”

“Favella, branch of hell, if not hell itself.”

-Carolina's diary, May 7, 1959

As a diarist reading Carolina’s diary, you have to understand what it takes to pick up a pen and notebook to write with an empty stomach, in a shack filled with mosquitoes, exposed to the elements, under a moldy cardboard roof, without knowing what you will do for food the next day. It’s easy for a reader to become enraptured in Carolina’s diary and thus amputate her from the poverty that violated her existence. It’s simple to reduce her diary to an intriguing novel; benefitting from a voyeuristic position instead of being present with Carolina’s living witness statement as an indictment of the very systems violating us today. The truth is, Dona Carolina’s diary IS a GREAT book to read, but because you are Black and woman and a diarist, this diary is a form of scripture for you to study and synthesise against the history you embody so that you can record and remember accordingly. In theory there’s no part of Carolina’s life that’s irrelevant to us.

The Weapon of Poverty

Poverty is not itinerant lack. Poverty is premeditated, observed violence and death machine, carefully constructed and engineered by the state. Poverty is a structural, systemic; a lower caste maintained through the vicious cycle of low wages and cost of living; exacerbated by factors such as social violence, food and medical apartheid, single-parenting, political neglect, commercial and corporate predation, greed, hyper-policing and systemic racism. It’s designed to be an eternal, immortal self-sustaining ecosystem of inequality and death, producing an ilk of desperation that society finds excuses to exclude. Poverty confirms the conspiracy against ALL of us, not just the few enduring lack.

Poverty is caste, stigma and stain. It’s eugenics. It’s hazing. It’s political. it’s a thief of destiny and identity. It’s a caustic solvent of dignity, continuing past the humiliation of being poor to creating social dynamics that remind the poor of their caste: be it school district zoning, the stores in the area, the advertisements allowed to plaster the horizon, the construction of housing units to shut out natural light, the location of public transportation and how clean the transit stop areass are; the presence/maintenance of sidewalks and public trash cans, the number of churches versus the number of companies where people can earn a living wage, the proximity to chemical factories, or the presence of certain books in the local library (if there’s one nearby).

“Due to the cost of living we have to return to the

primitive, wash in tubs, cook with wood.”

- Carolina's diary, June 16, 1958

“I was complaining to Dona Maria das Coelhas that what

I earned, wasn’t enough to keep my children.

That they didn’t have clothes or shoes to wear. And I don’t stop for a minute.

I pick up everything that I can sell, and misery continues right by my side.

She told me that she is sick of life. I listened to her lament in silence.

And told her: We are predestined to die of hunger.”

- Carolina's diary, December 11, 1958

You might ask yourself, why does any government benefit from an impoverished populace? Firstly, poverty serves as a control mechanism for the middle and upper classes, maintaining their compliance to the planation of imperialism, capitalism and fascism and quelling revolt against these systems lest they face the consequence of poverty. Poverty works to limit everyone’s imagination (not just the poor’s), creating the illusion that some are poor because they cannot manage resources and thus reinforcing the idea that by seeking to prove yourself responsible with your meager wages, the injustice of the wage system, the participation in maintaining corporate vested interest, you will not be condemned to be poor. Poverty maintains societal divisions that, if ever eliminated as the true enemy is revealed, would obliterate the need for the state and its control (hint, this is what the Black Panther Party proved once it united Appalachian whites, poor hispanics, and asians to the cause of Blackness and anticapitalism). Add the church’s message of prosperity where poverty is evidence of faithlessness and you have a watertight system of perpetual obedience.

One can also think of poverty as a hazing ritual, creating obeisance, wearing out its victims with fatigue, and extinguishing those capitalism deems “undesirable”. Democratic, imperialist fascist systems require inequality, serfdom and caste to reign. When there is economic soundness for everybody, a fascist system cannot control its population: once all of one’s basic needs are met they have time to think for themselves and will ultimately discover that the governing state itself need not be obeyed, paid, or maintained. Poverty is so violent that the sheer notion of the possibility for one to be poor is enough to fearmonger the general population to capitulate to larcenous, deleterious systems that offer success in exchange for obsequious participation. In such a system Black and indigenous peoples especially serve as sacrifices and portents to trick whites to pledge full allegiance so as to not end up like the lower castes. As Kenneth B. Clark explains, “The privileged white community is at great pains to blind itself to conditions of the ghetto, but the residents of the ghetto are not themselves blind to the life as it is outside of the ghetto.” Thus, forgetting the poor is forgetting the possibility for your government to be violent to anyone it deems fit— or to borrow the eugenicist term, unfit. The goal is obsequious workers, fodder for violence and thus hyper-policing, an inconsequential source of life-forces such as children, blood and plasma; and overall extermination of those who aren’t slowly killed by poverty.

“if the cost of living keeps on rising until 1960, we’re going to have a revolution!”

“When I was waiting in line to get some crackers, I listened to the women complaining. One told of stopping at a house and asking for a handout. The lady of the house told her to wait. The woman said that the housewife came back with a package and gave it to her. She didn’t want to open the package near her friends, because they would ask for some of it. She started to think. Is it a piece of cheese? Can it be meat? When she got back to her shack, the first thing she did was tear up in the package when she unwrapped it, out fell two dead rats.

There are people who make fun of those who beg.”

- diary entry, June 14,1958

Secondly, it’s useful to the powers that be to have a cheap labor source cornered by desperation for their basic needs, who cannot extricate themselves from bondage and oppression of meager resources; whose oppression feeds into pipelines of profit. This arrangement serves to justify capitalism’s mechinations. Meanwhile, impoverished zones are also used as hunting grounds by elites to stake out and select from desperate souls to see what pawn they can make out of them. Killing for sport. Scouting for athletic teams. Human and organ trafficking. The displacement of scorned professionals to be assigned to provide services in the area. A record labels and social workers with ulterior motives. Police with dirty intentions. Clark corroborates this,

“[The acting out rebel…point to the corruption and criminal behaviour among respected middle class whites. Almost every[one] in a Negro urban ghetto claims to know where and how the corrupt policeman accepts graft from the numbers runners and the pimps and the prostitutes. The close association, collaboration and at times identity of criminals and the police is the pattern of day-to-day life in the ghetto…they see the police as part of their own total predicament.

“…the white businessman has not stayed out of the ghetto. A ghetto, too, offers opportunities for profit, and in a competitive society profit is to be made where it can….

“Property— apartment houses, stores, businesses, bars, concessions, and theaters— are for the most part owned by persons who live outside the community and take their profits home.” (Clark, p. 14, 28)

In a white supremacist, capitalist system, poverty is designed to literally profit from the desperation of the destitute. Such desperation was Audalio Dantas’ appetite; the pill he crushed and snorted to profit from Carolina’s notebooks. There’s no ambivalence to how we should consider Dantas’ opportunistic predation of Carolina Maria and her exceptionality as a LITERATE favelado. In reading her notebooks we must frame his presence in her life as nothing save villainous and larcenous. We see that his “support” of de Jesus was contingent upon what her words could do for his career.

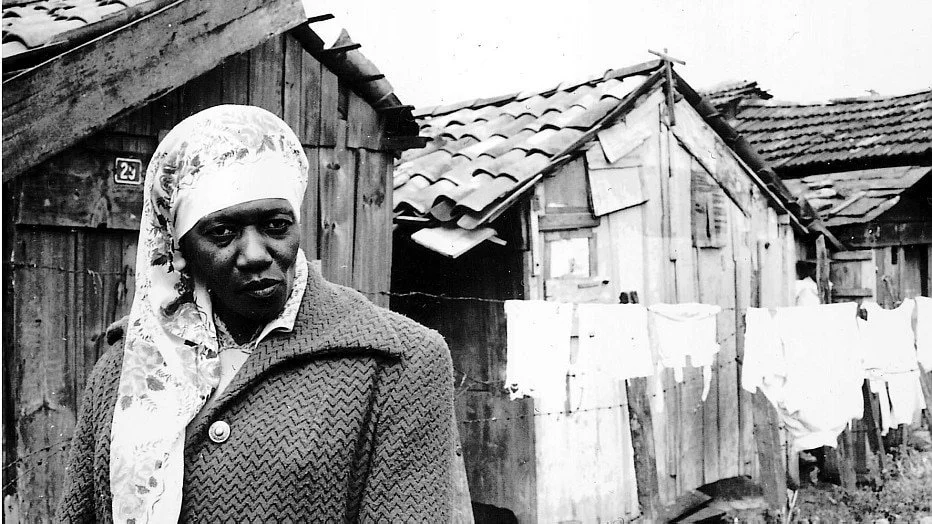

L-R: Carolina, Audalio Dantas, and Ruth de Souza in the favela.

Look at that smug look on the face of double-crossing hustler, Dantas. Nothing but a USER.

While Carolina’s poetic, prosaic diary-keeping illustrated the treacherous and destitute place she called home, knowingly addressing an audience beyond the favela (ultimately, the globe), and exposing Brazil’s racialized indecency with trenchant notes on the country’s systems, agents, outcomes, and vices, it wasn’t without the censorship of Audalio Dantas.. Today we understand that her anthropological notes were undergoing surveillance with that reporter who “discovered'“ her, the Audalio Dantas, whose monitoring and censoring of her work was committed in order to save Brazil’s face; to manage its PR (Note: Carolina’s unedited diaries would be published later on). As a journalist, Dantas was a handler and jury of Carolina’s witness accounts, and we should hate him for it, while praising Carolina for writing the truth she lived as she witnessed it, nonetheless. To this day the descendants of Audalio Dantas live off of the royalties of Carolina’s published diaries— her grandchildren DO NOT have access to this wealth.

Allow me to explain: as a journalist, Dantas’ work was to find a “good story” for his paper and its stakeholders. When he encountered Carolina Maria in a crowd, the journalist in him knew that he’d stumbled upon a goldmine. Carolina’s entries started off as weekly column in the paper where Dantas worked. Let me repeat that: every week her words were in the paper that EMPLOYED Dantas, yet she was NOT receiving ANY lick of PAY for her labor. Every week the citizens of Sao Paolo got their newspaper and read Carolina’s journal entries, imbibing her words like Hulu episodes— yet not one person that we know of ever sought to ameliorate de Jesus’ situation. How deranged do you have to be to casually read the anguished words of a mother digging dinner for her children out of the garbage and de-worming their bellies; losing weight and at times almost her mind—and then fold your paper back up and go about your day? That’s deeeeeep PSYCHOSIS; embedded classism and antiBlack racism that’s seared the conscience of those who benefit from these inhumane systems; who benefit from state-authorized, socially acceptable numbness to violence against Black peoples.

Not only is testimony of the desperate an economic category under capitalist regime, but also vice/addiction. In an intentionally depraved and depleted environment, vices apprehended by those entrapped and imprisoned by socioeconomics create economies that profit extraneous powers and business owners (drugs, alcohol..), petty to violent crimes create fines and bail bonds, economies of sex work form from desperation and not ease of choice; and countless opportunities for exploitation and corruption abound in the folds and crevices of blight. This is not conspiracy theory but conspiracy in practice, and it’s how you must imagine the unending possibilities of violence and its insensate, unconscionable agents. Are you able to comprehend how terrible the world actually is? Even in reading Carolina Maria’s words, can you construct the agenda of conspiracies still at work today?

“I have to admire these souls in the favela.

They drink because they’re happy.

And they drink because they’re sad.

Drink here is a comforter, in the sad as well as glad moments.”

- diary entry, November 22, 1958

The Black AND poor is another conundrum and catastrophe. Kenneth B. Clark explains that

“The poor are always alienated from normal society, and when the poor are Negro, as they increasingly are in American cities, a double trauma exists—rejection on the basis of class and race is a danger to the stability of society as a whole…

But because Negroes begin with the primary affliction of inferior racial status, the burdens of despair and hatred are more pervasive.” (Clark, p. 25, 27)

For Black peoples on the western hemisphere descended from the Middle Passage, poverty is especially a mechanism of CONTROL by the state. Control of our lives, purposes, the flow of our ideas, the quality of life for our children, to ensure they join the working [under]class, stripped of dignity, ideas and sensitivity to their brilliance— willing thralls. This is what Dona de Jesus unwittingly sought to save her children from; why she wrote so furiously to complete her first diary for publishing: she was focused on creating the opportunity to allow her children to live in peace and possibility, with agency and filled bellies.

“Lentils are 100 cruzieros a kilo, a fact that pleases me immensely.

I danced, sang and jumped and thanked God, the judge of Kings!

Where am I to get 100 cruzieros? It was in January when the waters

flooded the warehouses and ruined the food. Well done.

Rather than sell the things cheaply, they kept waiting for higher prices.

I saw men throw sacks of rice into the river. They threw dried codfish cheese and sweets.

How I innovate the fish who didn’t work but lived better than I.”

- diary entry, June 13, 1958

“I asked Senhor Dorio to come in. But I was ashamed. The chamber pot was full.

Senhor Dorio was shocked with the primitive way I live. He looked at everything surprisedly.”

- diary entry, December 27, 1958

Ultimately, poverty is a state-designed and sanctioned mass death sentence. It’s a set of hurdles designed to be insurmountable and inescapable, not because the one living in poverty is talentless, immoral, lazy and valueless but because society benefits so long as there is an underclass, a caste guaranteed to not rise from what Carolina Maria de Jesus calls the “garbage room” of the nation. Throughout her diaries she documents the violence of poverty, its sabotage of one’s sojourn, and the socioeconomic devastation it causes in a place like the favela. It’s INCREDIBLY important that as we read de Jesus’ remarks about the squalidness of the favela, we also humanize her, considering her as if this was our own mother, remembering that she’s not passively recounting the favela as a horrible-but-distant memory but experiencing the gruel and press in one of its shacks, with the terror of starvation, the harrowing fear of not being able to feed her children, and the surrounding community of violence as a daily threat against she and her children’s lives. There are days Carolina doesn’t know will be her last. Times she is writing about being emaciated and dizzy with hunger… In order to indict the system of oppression she’s enduring, YOU as the reader must feel all of this, too.

“How horrible it is to get up in the morning and not havee anything to eat. I even thought of suicide. But I am killing myself now, by lack of food in the stomach. And unhappily I get up in the morning hungry.

— Carolina’s diary, July 24, 1958

“I met Dona Nené, director of a city school, and João’s teacher. I told her that I was very nervous and that they were times when I thought of killing myself.

She told me that I should be calmer. I told her that there are days when I have nothing to give my children to eat.”

— Carolina’s diary, July 28, 1958

“today, the children are only going to get hard bread and beans with farinha to eat. I’m so tired that I can’t even stand up. I’m cold. Thank God we’re not starving. Today he is helping me. I’m confused and don’t know what to do. I’m walking from one side to the other because I can’t stand being in a shack as bare as this. A house that doesn’t have a fire in the stove is so sad! And pots boiling on the fire also serve as decoration. it beautifies a place.”

“I got out of bed furious. With a desire to break and destroy everything.

Because I only have beans and salt.

And tomorrow is Sunday.”

“There are days when I envy the life of the birds. I’m so nervous that I’m afraid I’m going crazy.”

“I have been in the world for such a long time that I am sickening of life. Besides, with the hunger that I experience, who could live happy?”

Poverty is psychologically brutal, causing often-internalised torment manifesting as PTSD, autoimmune diseases, hypertension, anxiety, depression and other physical and mental health issues. It wrecks the nervous system. In my opinion, research into the intersection of poverty and Black women (especially Black single mothers) is generally ineffectual, watery. Little has been done to explore, itemize and synthesize the comprehensive detrimental ramifications that poverty bludgeons into the lives of Black women—especially Black single mothers. Sidereal research across the internet denotes that there are harsh realities faced by those living in poverty, but stop short of vivid descriptions that might cause you to act on behalf of those enduring poverty. I honestly believe data around poverty and Black people is monitored and truncated to keep a certain amount of blame focused on Black people. To prevent any researcher from forming a genealogy of systems that helps them connect racism, chattel slavery, the Confederacy, and present day low-income environments to a plot against Black lives.

“I’m confused and don’t know where to begin.

I want to write, I want to work, I want to wash clothes.

I’m cold and I don’t have any shoes to wear.

The children’s shoes are worn out.”

— diary entry, May 28, 1958

Furthermore, malnutrition, sexual predation, cost of living increases, childcare expenditures, workplace sexism, social violence, housing insecurity, etc. are a few of the aspects anatomizing life in poverty. It’s literally a comprehensive torture. Life is lived minute to minute, hour to hour, day to day myopic life, prohibiting many from seeing themselves beyond a few months much less into greater plans for the future. Living in poverty is living in observed systemic and social violence. Navigating a world where there is more than enough and yet you do not have enough is a form of torture. The ambush of compounding, intensifying economic, social and psychological depletion, is dehumanizing. And we must remember that this is the ambush through which Carolina Maria de Jesus is documenting her life. Carolina never says “depression” or “PTSD”, so it’s our job as Black women to read her words with pathos and empathy, naming what Carolina was more than likely experiencing mentally as she ambulated trash-strewn streets thinking about deworming her children, buying them new shoes, processing the domestic abuse brawl she’s passing, and hoping to collect enough paper to buy rice and beans and coffee. Her poverty makes American poverty look like wealth.

“I dressed the boys and sent them to school. I went out and wandered around, trying to get some money. I passed the slaughter house, picked up a few bones. Some women were pulling through the garbage looking for edible meat. They claimed it was only for dogs.

That’s what I say— it’s only for dogs…”

— Carolina's diary, August 2, 1958

A reigning dynamic to poverty is how it is torture chamber and labor camp. It mandates full alertness, heightened senses that can time travel and voracious strategy for daily bread. It physically wears someone out: sleep deprivation, noise levels (constant police and ambulance sirens BLARE the plausibility of crime or death), and low or poor calorie diets (hot Cheetos, Chinese foods, sodas, processed foods, fast foods, etc.). ENTRY In such a severe, war-like setting, simple things requiring money or payment take planning, scheming what monies will need to be where and how and when, etc. Living in lack is mental gymnastics. How can one ponder, ideate, and think much less imagine? The intent is that you aren’t able to muse, reflect or decide, only plow. Consider the schedule of a typical day in Carolina Maria’s life: awaking early to stand in line to collect drinking water for the day for she and her three children, Jose Carlos, Joao, and Vera Eunice. That spigot was the ONLY water spigot in the favela. After returning and preparing a humble meal, she’d return to the favela streets to rummage through garbage for food scraps, scraps of metal and paper to sell, and to do sparse grocery shopping if funds allowed. this was a typical day in her life. the cost of food and the chances of her children’s having a meal haunted her all day, everyday. And remember, Dona Carolina made time to write betweeen dawn and day or late at night (due to insomnia).

ENTRIES.

A Witness’ Code

“‘I’m going to write a book about the favela and I’m going to tell everything that happened here. And everything that you do to me. I want to write a book, and you with these disgusting scenes are furnishing me with material.’” — Carolina’s diary, July 19, 1955

“The good I praise, the evil I criticize.

I must reserve my soft words for the workers,

for the beggars, who are the slaves of misery.”

— Carolina’s diary, June 13, 1958

Poverty is a hit on one’s life, and it’s not supposed to leave anyone alive or able to identify its names, faces, or strategies of violence. It’s NOT designed to leave witnesses. And for THIS reason Carolina Maria de Jesus is a miraculous figure in Black [women’s diarist] history. Because of Carolina’s indicting comprehension of her status and the violence of poverty in a wealthy society established by chattel slavery, “Quarto de Despejo” in its censored state still managed shed light on Brazil’s treachery. It also exposed the country’s duplcity, boasting progress as a home to multiple nations much like USA (Japanese, Portuguese, Swiss, Lebanese…) but still containing slums where Black people rummaged through garbage for food, infant mortality was common due to unsanitary conditions, drunkenness brought communal harm due to selective policing, children had no shoes, and many starved. A country seeking to be accepted as progressive and liveable while being a death chamber for Black descendants of slavery. This was much like the USA’s grapple to save the face during the Cold War as nations around the globe skeptically gawked at the US’ supposed “freedom” and “liberty for all” when Klan violence and apartheid proved the barbarity of its government with Black Americans—also descendants of chattel slavery. America faced global castigations questioning the country’s legitimacy as a democracy. Like Black authors and activists in the era of Cold War USA, Carolina Maria de Jesus’ voice was a rip in the curtain that was creating a wilful blindness for those in Brazil and around the world.

Society doesn’t enable the emaciated, mentally-bludgeoned, ghetto and slum-dwellers to be literate or nourished enough to make the connections and form language delineating the conspiracy against them and the agendas forming fatal engineering. The sugary, red dye 40 drinks and processed foods do extra to calcify the pineal gland and infuse compliance drugs and other behavioural modifiers into the blood. Drugs are there to help forget. But Carolina and her expository writing style refused these vices, so her testimony survived the conspiracies engineered by the Confederacy. As any witness to a crime experiences, audiences attempted to discredit her; she was shunned and gatekept from upward mobility. But her notebooks’ relevance today proves the veracity and validity of her testimony. Proves that as a living witness, she broke the matrix by becoming the least likely trumpet to the injustice that is the design of poverty, unemployment, systemic racism, and all the violence corporeal to these. Living witnesses are threats to systems of violence, evil. The world works overtime to ensure that witnesses are punished or else eliminated because the power of a living witness is their ability to identify the perpetrator of a crime. In the instance of Carolina Maria de Jesus, the crimes were the violence systemic racism and poverty. The arrogance or the orchestrators to poverty and disenfranchisement is that none of their victims will be able to call them out. Carolina became the bane.

“Pitita ran out with her husband right after her. The children watch these scenes with delight. Pitita was half naked. And the parts that a woman should cover up were visible. She ran, stopped, and picked up a rock. She threw it at Joaquim. He ducked and the rock hit a wall, right over [an onlooker’s] head. I thought: she was just born again!

… When Pitita fights everyone comes to see. It’s a pornographic spectacle.

The children were saying that Pitita had lifted up her dress.

I went inside the house. I live there listening to Pitita’s voice.

The evening in a favela is bitter. All the children know what the men are doing…

With the women. They don’t forget these things. I feel sorry for the children who live

in the garbage dump, the filthiest placed in the world.”

— Carolina’s diary, November 17, 1958.

And while she does not consider herself to be revolutionary, Frantz Fanon would disagree, arguing that “it is clear that in the colonial countries [i.e. the Portuguese colonised Brazil] the peasants alone are revolutionary, for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain.” (Fanon, p.61)

“There will be those who reading what I write will say—this is untrue.

But misery is real. What I revolt against is the greed of men who

squeeze other men as if they were squeezing oranges”

— Carolina’s diary, May 29, 1958

We can appreciate the above entries as demonstration of Carolina’s unflinching naming of names in her diary. This is another trait of bearing witness that unnerves the oppressor: the ability to NAME things and call NAMES. The naming of names is a practice of AUTHORity and

“Here in the favela there are those who build shacks to live in and those who build them to rent. And the rents are from 500 to 700 cruzieros. Those who make shacks to sell spend 4000 cruzieros and sell them for 11,000. Who made a lot of shacks to sell was Tiburcio”

— Carolina’s diary, May 30, 1958

“I decided to take the street car and go home.

We were talking about Dr. Adhemar, the only name that we can blame

for the rise in the cost of transportation. A man told me that our politicians are clowns.

I think that Dr. Adhemar is angry, and he decided to be forceful

with the people and show them that he had the strength to punish us.”

— Carolina’s diary, November 4, 1958.

“More new people arrive in the favela. They are shabby and walk bent over with their eyes on the ground as if doing penance for their misfortune of living in an ugly place.

A place where you can’t plant one flower to breathe its perfume. To listen to the buzz

of the bees or watch a hummingbird caressing the flower with his fragile beak.

The only perfume that comes from the favela is from rowing mud, excrement, and whisky.”

— Carolina’s diary, May 30, 1958

The diarist practice was in every element Carolina Maria de Jesus’ resistance to the agenda of poverty as a destiny-snatcher, child-violator, life-interceptor and caste-reinforcer. Carolina was acutely aware of her warfare; the long-term impacts the favela would wreak on she and her children if she didn’t exercise any form of agency to resist external forces encroaching upon her family. And she resisted. Throughout her diaries we become aware of her value system: her personal code of ethics that kept her treacherous outside world from coming into her inner world. She mentions selective alcohol intake, not speaking to men about sex (“I don’t speak pornography”), conscientiously choosing her dignity despite the serried undignified dynamics flanking her, nurturing her mind with books and magazines, writing, and the radio whilst those in her surroundings passed their free time in drunkenness or some other stupor. She did her very best to mind how involved she would get in the affairs of domestic abusers, brawling neighbours, drunken parties, or unproductive conversations. This was her assertion of dignity in a world that imposed circumstances and torture onto she and her children. Huey P. Newton wrote of how “…people who work and struggle and suffer much are the victims of greed and indifference…. The causes originate from outside and are imposed by a system that ruthlessly seeks out its own rewards no matter what the cost in wrecked human lives” (Newton, p. 42). Powers that be create undignified scenarios to cause witnesses to shed of their dignity in order to survive; and from that action, to surrender their will to testify against said powers. But Carolina was an anomaly.

From her practices of subversion to the conspiracies against her discernment and LIFE, we as Black women diarists can ascertain ideas on how to wisely conduct ourselves in serried circumstances where venomous, spiteful, lethal dynamics flank us, and we are still called to function in the integrity of our birthright. We can learn that we too must create not only survival strategies but also personal codes of honor where we refuse obeisance to desperation and tell ourselves where our boundaries lie for sake of self and those beyond. What are you NOT willing to do? What will you NOT choose, become, eat, drink, watch or listen to so as to protect your living witness accounts?

“Yesterday I drank beer and today I want another. But I’m not going to drink. I don’t ant that curse. I have responsibilities. My children! And the money that I spend on beer takes away from the essentials we need. What I can’t stand in the favela are the fathers who send their children out to buy pinga [a brand of liquor] and then give some for the children to drink.”

— diary entry, July 19, 1955

“While I was waiting for the ink, a white man that was nearby asked me if I knew how to read. I told him I did. Then he picked up a pencil and wrote:

‘Are you married? If not, would you like to sleep with me?’

I read it and handed it back to him, without saying anything.”

— Carolina’s diary, August 30, 1958

Conclusion

“ the old people say that at the end of the world life is going to be empty and drab.

I think that’s pure talk, because Nature continues to give us everything.

We have the stars that shine. We have the sun that warms us.

And the rains that fall from high to give us our daily bread.”

— Carolina’s diary, December 20, 1958

Combined with antiBlackness and systemic racism, the violence of poverty is designed to strip one of their humanity and dignity such that impoverished environments take a distinct character that inadvertently transfers to all living in it: violence, vice, unpolished language, demoralisation, blight, disinvestment, abandonment, unattended children, dejection and bad actors whose actions and behaviours also shape the environment. This is why people seek to escape it. People like Carolina Maria de Jesus. Furthermore, poverty and slums/ ghettos/ favelas in tandem are premeditated environments of societal disinvestment. They create societal excuses for obsequious compliance with a fascist system, while manufacturing an underclass whose understanding of the system’s engineering but lack of power to change it or literacy to denounce it creates a convenient gap whereby injustices can continue. This is also why Carolina’s literacy is the protagonist, the heroine in her story. Her notebooks reveal a strategy of capitalist systems: Illiteracy enabled such that the victims of the systemic crimes of systemic racism and poverty cannot employ the force of language to indict said systems. Thus, Dona Carolina’s existence was an anomaly, a slip through the cracks of violence where she evaded its mold of illiteracy and was able to WRITE the tale.

My encouragement to you: intentionally, engage Dona Carolina’s words. Dig deep and deal with her notebooks like you are handling a holy text, carrying a voice that’s been preserved through the eras in book form. This is living witness testimony. Recognize her sagacity in keeping to her conviction and recording matters that impact not just she personally but all oppressed peoples. The evils she faced are still working against us in these devilish systems! Her writings are evidence and plumbline to which we can hold fast in our testifying against the relentless wickedness that demeans and dehumanizes Black peoples everywhere. We can hold her truths in our hands in the form of her diaries and be comforted and assured that someone dared to denounce, decry and resist accepting state-sanctioned antiBlack disenfranchisement.

And from this place we can Journey Soulfully.

Citations:

Clark, Kenneth B. Dark Ghetto: Dilemmas of Social Power. Harper & Row, 1965.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Constance Farrington, Penguin Classics, 1968.

Newton, Huey P., and J. Herman Blake. Revolutionary Suicide. Penguin Books, 1973.